Royal Palace Museum, Luang Prabang

As palace’s go the Royal Palace in Luang Prabang, Laos, is somewhat humble. Do not expect the vast manicured grounds of Versailles, or the sumptuous decorations of the palaces of the Vatican even if the steps leading to the main entrance are Italian Marble. The architecture, like many of the buildings on the peninsular, is Lao and French beaux-arts style. The palace was built in 1905 and was the home of the Lao royal family until 1975. The monarchy was in place for some 600 years; the last one hundred years or so it coexisted uneasily with the colonising French.

What struck me immediately we entered the Palace was the absence of a guide book, or explanatory notes beyond the most basic of labels. I’d done very little preparatory reading. I only knew that the last King of Laos, I didn’t even know his name, (he was known as Savang Vatthana) had lived there until he was deposed. I’d been counting on a guide book to fill in the gaping holes in my knowledge.

I was also struck by the ostentation of the throne room, one of the first rooms visitors see. There, seated on a golden throne, the Kings of Laos were crowned with a crown unlike any other I’ve seen. It’s tall and rises to a point – I’m sure there is great significance to its design. It seemed to echo the shapes and designs of the Stupa I saw during our travels. The king’s scabbard, even his shoes were gold. The walls of the room were decorated in Japanese lacquered glass. It was all very ornate.

There was a disapproving tone to the few labels that did exist. They declared that the King, and I’m not sure now whether it was King Savang Vatthana or his father, King Sisavang Vong, commissioned the crowns, the decoration of the throne room, all the golden regalia specifically for the coronation. Predictably, I thought: this is so ostentatious it’s offensive. Laos was and is a poor country, ran my internal dialogue. The King had all this when people in his country were most likely starving.

And yet, I admired the beauty of these jewels. I wished I’d been at that coronation. I’m sure it would have been an exotic, mysterious, spiritual, and grand sight. Photos are prohibited in the museum and I can tell you my cell-phone, which was in my pocket, burned hot with temptation.

I wandered from room to room, the cool airiness a relief from the humidity and heat of the afternoon sun. The rooms, other than the throne room, were plain, even humble given it was a palace. It was like wandering through an empty home, its owners long gone, their ghosts lingering, as in any good Bradbury story, in every shadow, in each abandoned treasure.

I noticed etchings on the walls, placed so that as visitors walked from room to room they could study a new scene. They illustrate a famous Laotian legend – the story of a prince who forsook the riches of his kingdom, and with his wife and children, set off in search of a simpler way of life. Along the way he gave away first his goods, then his cart, then his horses. Only after giving up his children is he reinstated as king. It’s a version of a traditional story told in Theravada Buddhism, that teaches the value of perfect charity. I wondered why, of all the legends, this particular one, here in the palace.

In the last room I viewed there was a photo of the King with Ho Chi Min. Remember him? He was the communist leader of the Viet Cong. They were dancing together with traditional Lao dancers. Also on display in that room were gifts to the Kingdom of Laos from many different countries: China, Vietnam, Japan, and the US, to name only a few. Interestingly, Australia gave a boomerang. I began to garner a sense of a man who, due to geography (five larger and more populated countries border his country) and happenstance (during his reign Lao was involved in the second Indo-China War and then a civil war) was required to exercise the greatest of diplomatic skill.

There was nothing to tell me, in what was once his home, what had become of him and his family. It was as if they had simply disappeared.

As I exited the museum I wondered, what have I just seen, what exactly have I been told? Thinking I must have missed something I went through the exhibition rooms again.

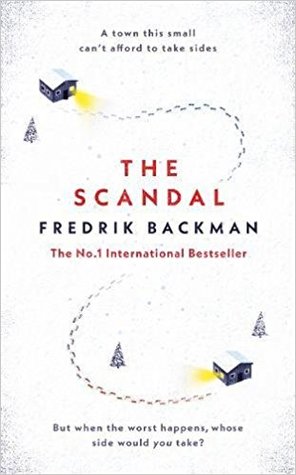

Coincidentally, I’d been alternately reading and listening to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 as we travelled around Northern Laos. This great classic describes a dystopian future where books are banned. Without access to history or culture the population is easily controlled. It’s a world where the masses accept the comfort of distraction (curiously, in a brilliant piece of prescience from Bradbury, people spend inordinate amounts of time gazing mindlessly at screens which stream low quality content) rather than the discomfort that comes with paying attention. Freedom of expression has disappeared and few seem to mind. Neighbours dob in book owning neighbours, who then get a visit from the fire service. In this world where houses are fireproofed firemen burn books.

As I struggled to understand what I was looking at in the Royal Palace, I thought about Bradbury’s dystopian world. About how easy it was for that regime to control its population through controlling the stories, and through fear.

I remembered the scene very near the beginning of Fahrenehit 451, when our yet to be hero, Montag encounters Clarisse. From what seems to be the most innocuous of conversations Montag begins to notice, to really notice the world around him. And once he notices everything changes. It turns out that paying attention is a subversive act.

I emerged from the palace with the uncomfortable feeling that I was supposed to think the grandeur, such that it was, was bad. That the King and his family had enjoyed privilege beyond what was reasonable. And I don’t think I was supposed to notice what hadn’t been said, much less ask any awkward questions.

John and I found a shady spot in the palace gardens. What ever happened to the king we asked each other and then Google.

I was surprised Google could give us an answer. The press in Lao is, as I understand it, strictly regulated. Google actually gave us several answers, they vary according to political leaning.

According to Wikipedia, after the Lao Pathet took control, King Savang Vatthana refused to leave the country. He and his family were moved out of the palace to a nearby residence. For a brief time he had the titular role of Supreme Advisor to the President. But he was without influence. It wasn’t long before, he, his Queen, and their children were moved to a re-education camp in the far north. Many dissidents and opponents of the new regime, who did not join the Lao diaspora, were sent to such places. The King, the Queen and the Crown Prince died – it is said from malaria.

In Fahrenheit 451, when Montag dares first, to steal a book, then to read it, it seems that the regime is all knowing and all controlling, that the outcome for our reluctant and flawed hero can only be bad.

But futile, or not, Montag must resist. And he discovers there are others like him. People who, at great risk to themselves, have made it their business to remember and tell each other the forbidden stories. All is not lost.

Near the end of the book Granger, Montag’s mentor, tells him:

‘“I hate a Roman named Status Quo … Stuff your eyes with wonder,” he said, “live as if you’d drop dead in ten seconds. See the world. It’s more fantastic than any dream made or paid for in factories. Ask no guarantees, ask for no security, there never was such an animal. And if there were, it would be related to the great sloth which hangs upside down in a tree all day every day, sleeping its life away. To hell with that,” he said, “shake the tree and knock the great sloth down on his ass.”’

Not a bad way to approach life, where-ever you live, what-ever your circumstances, what-ever the regime.

WordPress Daily Prompt: A House Divided

Categories: Laos, Off-shore Adventures, On Books

Definitely a very humble abode for a palace, or at least what we are used to seeing for a palace.

LikeLike

How easy it is now to find answers to questions with the ever present Google (assuming there is an internet connection). We are so used to all palaces, museums art galleries giving a full description of what we are looking at that I can understand how frustrating it would be with no descriptions and how VERY frustrating not to be able to take photos…

LikeLike

The no photo rule was the most difficult of all – those crown jewels were exquisite. I think maybe it’s quite a common rule. Ben was telling me this morning that photos are prohibited in the Basilica at Assisi. (He’s in Italy at the moment.) And I seem to remember a no-flash rule in the Sistine Chapel – that was fourteen years ago, so my recall might be faulty.

LikeLike

Did they have postcards on sale? I sometimes think the no photo rule is to encourage the sale of postcards….

LikeLike

No, no postcards at all. And no images anywhere on the internet, either.

LikeLike

Pity about that…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gold shoes, that’s luxury indeed!

LikeLike

Isn’t it just. I imagine they would be rather heavy which might mean very tired feet at the end of all the celebrating.

LikeLike

True!

LikeLike

This was great to read. Part travelogue, part poignant tale and part warning/wake up call. I found myself slipping between thinking about reading more about Laos, retreading Faranheit 451 and taking a history class. I love how you wove this all together. Great job.

LikeLike

Fahrenheit 451 was on my must read list and I finally got around to it on this trip. I had no idea at all what it was about before I started reading it. Strange how things work out, sometimes.

LikeLike

what a cool palace – and you are right – very humble – for a palace

and I enjoyed the way you share some thoughts – like this….

“About how easy it was for that regime to control its population through controlling the stories, and through fear.”

and I agree w/ the ending quote- not a bad way to approach life 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Yvette. Interestingly, in Fahrenheit 451 one of the characters observes: “The public itself stopped reading of its own accord.” A shocking idea on one hand and yet very easy to believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The co relation you have made with the strict regulation in Laos and the movie is really very interesting. I an fortunate to be in a world where I am allowed to see, think and expand my mental horizons.

LikeLike

To not have that right would be very challenging.

LikeLiked by 1 person