“The open road speaks for a perpetual becoming.”

Pico Iyer

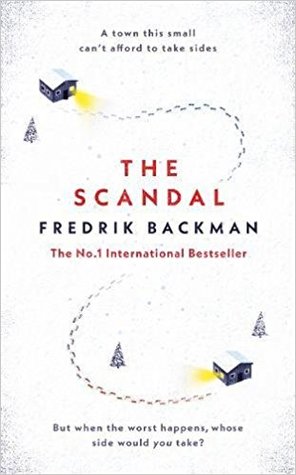

I’m continuing my tradition of reading well-known books years after they came to the attention of the rest of the world! But the gap is narrowing. Pico Iyer’s The Open Road was published six years ago, where as One Hundred Years of Solitude and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, both books I’ve discussed previously, were published in 1967 and 1969 respectively.

Friends have recommended Pico Iyer to me many times. When they’ve done so its been in the hushed tones reserved for the much admired. But I’ve previously found his writing inaccessible, his sentence construction complex. Not far into The Open Road, The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama I was confronted by a sentence the length of a decent paragraph, with multiple clauses and sub-clauses. It required concentration. I had to pay close attention to the commas and the semi colons but the reward was the realisation there really was no better way, no more efficient way to present the ideas discussed. This proved to be an interesting parallel to the teachings of the Dalai Lama. He emphasises that understanding requires effort.

In fact, Iyer includes a relevant anecdote, one that still has me laughing with recognition.

Apparently, whenever the Dalai Lama speaks to a Western audience, always someone asks how to fast track the journey to enlightenment. Not only has the questioner missed the point entirely, but it’s Western attitudes in a nut shell.

For me The Open Road is the right book at the right time – even if that right time is several years after the rest of the world. My most recent travels (and those planned in the foreseeable future) have exposed me to Buddhist cultures, albeit a different school of Buddhist teaching than that of the Tibetan tradition. Nevertheless, those travel experiences have reminded me of matters that I was fascinated by as a girl and then later, as a young woman.

When I was ten, maybe eleven, an adult friend of my parents, a young Mum at home with little children, had a book that intrigued me. On the cover was a man with a third eye in the middle of his forehead. What soon to be teenager wouldn’t be curious? I inveigled the book from her and read it from beginning to end. Mum and Dad thought it was some kind of science fiction which, as it turns out, is probably closer to the truth than was commonly accepted at the time. It was an account of Tibetan Buddhism that, in comparison to the rather dry Sunday services my sister and I were sent to each week, could only be described as exotic and intriguing. Most of it was way over my head! It was also a hoax.

A little over ten years later I, like a lot of young Catholics at the time, was reading Thomas Merton. He was a Cistercian monk and, like me, a convert. He was interested in the practice of the contemplative life in other traditions, particularly, but not only, Buddhism. Sadly, he died in Bangkok, in December 1968, not long after meeting the Dalai Lama. How I would have loved to eavesdrop the conversations between those two men.

The Open Road was a bit like that – eavesdropping. I got the sense these two monks thoroughly enjoyed their meetings; that they discussed the business of living their lives as monks rather than the dogma of their traditions and in doing so, despite vast differences, realised great similarities.

Pico Iyer writes with a powerful immediacy so that I often felt as if I was listening in on conversations as they happened. I was sitting beside the young Pico’s father while he told his son the story of a boy prince (The 14th Dalai Lama, in actual fact) who fled his country to escape his enemies. It was a story in which, as Iyer says, “Right had not exactly won but had managed to keep one step ahead of wrong.” I too was in Dharamsala the day the Dalai Lama opened a temple funded by Australian Buddhists. Iyer describes them, “smiling beautifically in their white scarves”. (Much as I imagine I might smile should I ever have an audience with the Pope, or for that matter with the Dalai Lama). And I might have been sipping chai tea at a nearby table, my ears flapping, as Iyer discussed the future of Tibet with Lhasang Tsering- a conversation that revealed the frustration of some Tibetans at the non-violent response by their government to the Chinese occupation of their country.

Iyer has said he saw in this book an opportunity to bring the ideas and the teachings of the Dalai Lama up against the realities of the world. In doing so he also shows a man who has an impish sense of humour, an infectious giggle and an insatiable curiosity about the world. A man, although revered by his people as a God, who describes himself as a simple Buddhist monk, who rises every morning at 3:30am to meditate for four hours about “the roots of compassion and what he can do for his people, the “Chinese brothers and sisters” who are holding his people hostage, and the rest of us, while also preparing for his own death.” And as a result of decades of study he’s able to distill the teachings of Buddha for an international audience. Iyer says: “He once distilled Buddhism into six words: Change is part of the world.”

The Open Road is a counter point to the exotic that was presented to me in The Third Eye, the fanciful notion of Shangri-La made popular in the book by James Hilton, and the overly simplified, but perhaps nevertheless helpful, teachings of mindfulness that are now being presented throughout the western world as treatment for the scourge of depression and anxiety.

The book draws on a thirty year relationship between Iyer and the Dalai Lama. And it’s supported by vast background reading. (A reading list is provided for those who wish to read more. It’s a practical sort of a list. It includes the Scorsese film Kundun – I might start there.) Iyer hoped that by publishing the book in 2008 prior to the Beijing Olympic Games, he might contribute in some way to a shift in the attitude of the Government of China towards Tibet.

The Beijing games have come and gone, the years have passed and the hoped for change Chinese government’s attitude to Tibet is yet to be realised. However, the Dalai Lama himself says that “until the last moment anything is possible.”

When I think of Dharamsala, in my mind’s eye I picture a back backers destination – an international and ever changing community of travellers moving in their own microcosm from one destination to another. I tend to avoid such places. Perhaps it’s also like the Via della Conciliazione in the Vatican City with one important exception: The Vatican is recognised internationally as a state in it’s own right. As you approach St Peter’s Square, especially on foot, there are many vendors hawking rosary beads and statues of Mary and other religious items. To some that is off-putting, even shocking. But there is layer upon layer of meaning in such a place. Yes, some are purchasing souvenirs. But for others those same purchases have deep and long lasting significance – they are symbols of pilgrimage, a journey, their personal open road.

Reading The Open Road has taken me back to the fanciful Tibet of my girlhood and forward to the Tibet of our day. Now, I have a sense of the Tibet in exile. And of occupied Tibet. Perhaps, one day, I’ll be able to visit both. Most of all, despite the convictions of the author and his subject, this is a book that reveals rather than exhorts. How much it reveals depends on what the reader brings to it. I expect I’ll be thinking about it for a long time.

Have you read The Open Road? What did you think?

Have you visited Dharamsala? Or Lhasa? What were your impressions?

Categories: Off-shore Adventures, On Books

![His Holiness, The Fourteenth Dalai Lama At_the_Unsung_Heroes_of_Compassion_event_San_Francisco by Minette - Flickr: [1]. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons. His Holiness, The Fourteenth Dalai Lama At_the_Unsung_Heroes_of_Compassion_event_San_Francisco by Minette - Flickr: [1]. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.](https://jillscene.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/at_the_unsung_heroes_of_compassion_event_san_francisco.jpg?w=271&h=300)

“Understanding requires effort” could also describe our experiences in Tibet. It does require quite a bit of effort to cope with the situation. But on the other hand, it is also a very rewarding experience. Will definitely read the book!

LikeLike

If you get the chance, please let me know what you think of it – especially in light of your experiences there.

LikeLike

Sure, I’ll let you know!

LikeLike

It’s on my ‘to read’ list, as Tibet has always been a place that appealed to me. You must visit, for both of us, Jill 🙂

LikeLike

Fingers crossed, Jo, fingers crossed!

LikeLike

Excellent review, Jill – beautifully written. Although I haven’t been to Tibet (yet), I have been to Nepal which has a fascinating spirituality. Now I hear Tibet calling. Thanks! 🙂 ~Terri

LikeLike

Thanks, Terri, I’m glad you enjoyed it. The book is a memorable read and it made me want to visit that part of the world, too.

LikeLike

What an eloquent review! I have not read the book or been to Tibet. I seem to be saying I have not been to a lot of places recently. You are definitely stirring up my Wanderlust Jill!

LikeLike

I hope stirring up wanderlust is a good thing! I’m glad you enjoyed the review, Sue.

LikeLike

Oh definitely! 🙂

LikeLike

you write so well jill!

and my take away is much, but real quick – said uh-huh to this: “understanding requires effort” –

and enjoyed the bike photo – and it is crazy how it feels like 2008 was just yesterday – so I like how you noted the date of the book release and all that.

and fast track to enlightenment – yup – that is what we all sorta want and expect – instant – quick and yesterday – ha! but it doe snot work that way, eh?

and had to laugh when you said the third eye on the forehead. And this is not meant to be disrespectful, but recently I was telling someone about a job I had at a comedy club back in the early 90’s – less than 2 weeks – and well, it was fun – but one of the comedians and a joke about walking up and rubbing off one of those forehead dots and underneath it said “free slurpee” – okay – totally disrespectful – sorry – but it was funny.

LikeLike

That bike photo is a classic, isn’t it! Mum made those outfits for us. I was always in pink or red, my sister in blue. I’m glad you enjoyed the post, Yvette. Writing it helped me to formulate my thinking about the book.

LikeLike